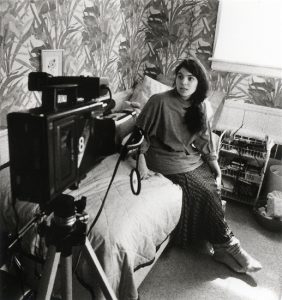

By Judith Helfand, filmmaker of “A Healthy Baby Girl”

In the 1990s, as a young woman at the beginning of my social change filmmaking career, I had an experience that pushed me to turn the camera on myself. I’d never had intentions of filming my own family. I thought, what would a middle class Jewish family in Merrick Long Island have to offer the world in terms of struggle? We we were your average consumers who had enough resources to do what we needed, pursue the education we wanted. But this was before I learned that we consumers had been consumed by short sighted big pharma business decisions. Decisions that on a mega company balance sheet added up only to a calculated business risk, but for me added up to a lethal form of cancer that threatened my life as much as it did my precious relationship with my mother.

In the 1990s, as a young woman at the beginning of my social change filmmaking career, I had an experience that pushed me to turn the camera on myself. I’d never had intentions of filming my own family. I thought, what would a middle class Jewish family in Merrick Long Island have to offer the world in terms of struggle? We we were your average consumers who had enough resources to do what we needed, pursue the education we wanted. But this was before I learned that we consumers had been consumed by short sighted big pharma business decisions. Decisions that on a mega company balance sheet added up only to a calculated business risk, but for me added up to a lethal form of cancer that threatened my life as much as it did my precious relationship with my mother.

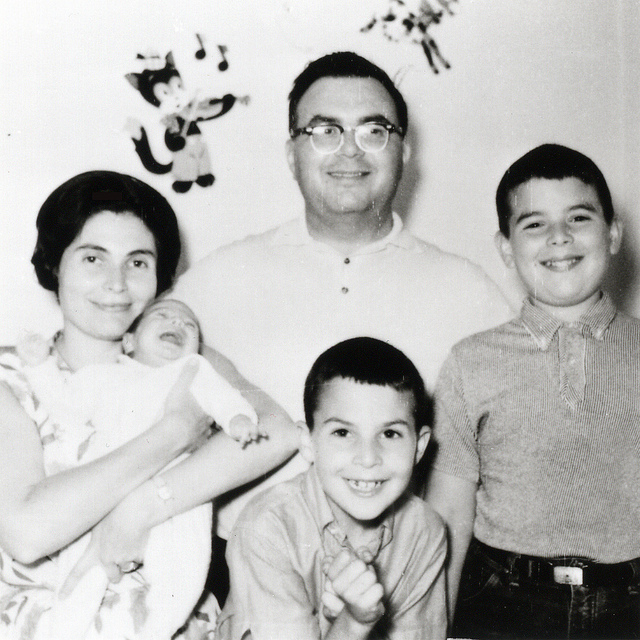

In 1962, when my mother Florence was pregnant with me, she was prescribed an anti-miscarriage drug called diethylstilbestrol (DES). Twenty-five years later I was diagnosed with DES-related cervical cancer. After a radical hysterectomy I returned to my parents’ home in Merrick, Long Island to recover. I wanted to use my camera as witness, to remind both my mother and I that we were not alone, and that the unchartered emotional territory we were suddenly navigating was something we shared with at least five million other DES mothers and five million DES daughters and sons living in the U.S.

From 1947 to 1971, doctors prescribed DES, a form of synthetic estrogen, to millions of pregnant women. Some early scientific studies questioned the drug’s usefulness, finding it to be carcinogenic to laboratory animals and ineffective at preventing miscarriage; by 1970 doctors had identified a rare form of vaginal cancer in some young women exposed to DES in utero, the same cancer I was diagnosed with at age 25. It’s one thing to understand the danger of hormone-mimicking chemicals intellectually and another to experience those impacts on your own body. To see what human extinction means every time you look in the mirror and know that your Grandma’s eyes and your Dad’s eyes and your eyes will never be passed on to your children.

As I began to film, I realized that the real story about the human, personal and long-term impact of these chemicals—which range from prescription reproductive technology to the pesticides or industrial solvents so many workers are exposed to in the fields and in factories—would never be revealed in a product liability courtroom. In my mind the story was playing itself out behind the closed doors of suburban starter ranches, like my parents’ home in Merrick, Long Island.

In many ways it was a relief to translate my own grief and pain into a full on documented and scientifically sound story that could help reframe the discussion around chemicals and toxics to include the families and the emotions, that could help place extreme love and parenting at the very center of the discussion rather than at the periphery. This discussion continues today and I’m convinced that the only way we’ll change this issue is by massive collective mobilization with unlikely partners who have stories like mine, who are inextricably connected through the chemicals that are in their bodies, that informed or possibly deformed their children’s health, present and future. Our federal laws on toxic chemicals are completely broken and must be reformed to protect public health. (See below for links to specific actions.)

In many ways it was a relief to translate my own grief and pain into a full on documented and scientifically sound story that could help reframe the discussion around chemicals and toxics to include the families and the emotions, that could help place extreme love and parenting at the very center of the discussion rather than at the periphery. This discussion continues today and I’m convinced that the only way we’ll change this issue is by massive collective mobilization with unlikely partners who have stories like mine, who are inextricably connected through the chemicals that are in their bodies, that informed or possibly deformed their children’s health, present and future. Our federal laws on toxic chemicals are completely broken and must be reformed to protect public health. (See below for links to specific actions.)

My family’s personal life became the stuff of public record. Our connection was tested in complex ways I never could have imagined: we experienced the kind of guilt, stress, anger, pain and mourning that does not come with a map, a memo, or a navigator. Determined not to let all of this permanently change my relationship with my mother, I turned on my video camera and ironically, it was there, from the other side of my camera, that my mother taught me about the lengths a parent will go to protect or at least heal her child. It was here that she truly taught me about parenting and motherhood. And I will forever be grateful.

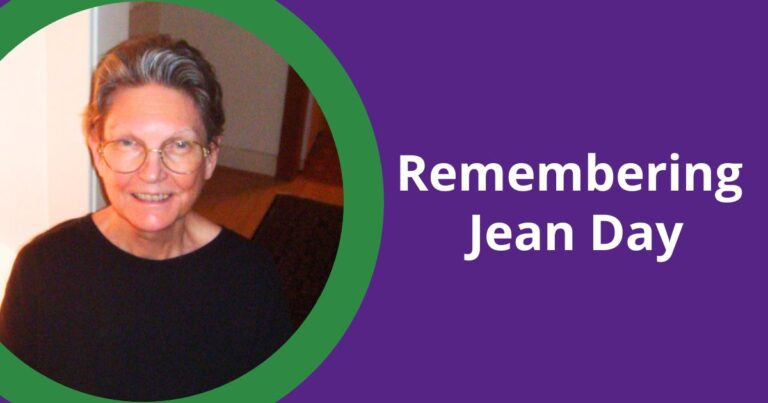

My beloved mother Florence passed away after her own battle with colon cancer this past year. A few months ago, facing the prospect of my first mother-less Mother’s Day, I decided to make the film available online digitally for the first time, as a way of commemorating the journey we went through together, to share a story that is still very relevant today.

My beloved mother Florence passed away after her own battle with colon cancer this past year. A few months ago, facing the prospect of my first mother-less Mother’s Day, I decided to make the film available online digitally for the first time, as a way of commemorating the journey we went through together, to share a story that is still very relevant today.

It was while I was both grieving my mother and preparing for this launch that the greatest surprise happened: I received a call from an adoption agency, Forever Families Through Adoption, that I’d had been working with for the past four years. I had four hours to say yes to a baby that would be born the next morning and within four days I welcomed a healthy baby girl into my own home and became a mother myself. This Mother’s Day, which is full of meaning for so many reasons, I am reminded of the unexpected ways in which our family stories can weave together, our relationships can strengthen in the face of challenges, and I can become more committed than ever to creating a toxic-free future for my own daughter Theodora Feyge in the name, memory and honor of her beloved grandma Florence.

Judith Helfand’s film, which premiered at Sundance in 1997 and won a Peabody Award, is now available to rent or download on itunes. Join the movement to reform our federal laws on toxic chemicals by signing this very important petition to Congress. Also urge the nation’s top ten retailers to get serious about moving toxic chemicals out of the supply chain and Mind the Store.