The chemical industry’s attack on a recent TSCA reform proposal is revealing and ominous.

That famous line from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” – commenting on the corruption, decay and strange goings on in the fictional Danish court – came to mind recently in relation to chemical reform and Congress.

That famous line from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” – commenting on the corruption, decay and strange goings on in the fictional Danish court – came to mind recently in relation to chemical reform and Congress.

Unless you subscribe to a small number of specialty news services, you likely missed a major development in TSCA reform in the last few weeks. The Democrats on the relevant House subcommittee proposed fixes to the Chemicals in Commerce Act, the deeply flawed reform legislation sponsored by the subcommittee’s chairman, John Shimkus (R-IL). Rather than engage on the proposed fixes, the industry dismissed it categorically and announced it would shift its focus to the Senate. Chairman Shimkus then postponed action on his bill indefinitely. While putting the brakes on his deeply flawed bill is technically good news for reformers in the immediate term, the industry reaction has dark implications for the future of TSCA reform and suggests that – as in Hamlet – things may be even worse than they seem.

Democrats’ suggested compromise was rejected

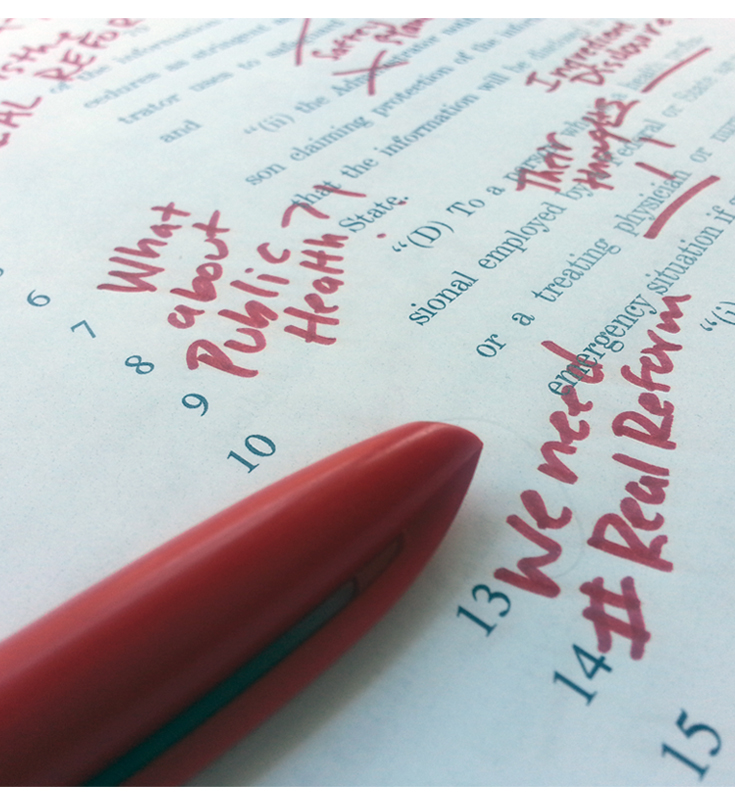

You may remember that in the last hearing on the Chemicals in Commerce Act, the Democrats accused Chairman Shimkus of not negotiating over his bill. Mr. Shimkus for his part said the Democrats had never provided legislative language that he could review. The Democratic members then met and decided to offer language, which they did three weeks ago. The proposal was in the form of a “redline” meaning it literally took the bill and proposed portions to be cut and new language to be added. (Though it was not initially a public document, an industry law firm has posted it online here.)

Details of proposed “redline”

The proposal is the first public document to show exactly how – in black and white – the problems with the House bill could be fixed. Almost all of the fixes would also apply to the Senate bill. For example, a major claim made for both bills is that they “fixed” TSCA’s safety standard. Nearly everyone outside of industry – including the EPA – has disagreed – saying that the bills would retain the key elements of the current TSCA that prevented EPA from even regulating asbestos. Both bills also fail to protect vulnerable populations (like pregnant women and children) or require that all known exposures to a chemical be added together to get an accurate picture of the chemical’s risks. Similarly, the current TSCA has a requirement that EPA choose the “least burdensome” way of restricting a chemical. In practice, this led to “paralysis by analysis” and was an issue in the court rejecting EPA’s attempt to restrict asbestos. Both bills effectively require the same paralysis but with different words.

The Democratic proposal addresses these flaws rather simply, by adding a definition to the beginning of the bill that would change TSCA’s standard to be strictly health-based and require protection of vulnerable populations from known exposures to the chemical taken together (called “aggregate exposure.”) It gets rid of the “least burdensome” problem, instead requiring EPA rules to be “cost effective.” It makes these changes with very few words, showing how simple it would be in fact, to fix key problems that have bedeviled both bills.

The proposal goes on to address other problems. Backers of both the House and Senate bills, for example, originally said they would improve EPA oversight of new chemicals. Critics, including the EPA, quickly pointed out that in fact both bills would weaken EPA’s oversight of new chemicals. The proposal instead mildly improves EPA’s ability to spot and intervene when a new chemical raises “red flags.” Both bills also require EPA chemical reviews to be limited to a chemical’s “intended conditions of use.” While at first that sounded innocuous, the recent spill of a hazardous chemical into the Elk River in West Virginia showed how the phrase could easily become a “weasel word” since obviously no one intended for the tank holding the chemical to rupture. Again the proposal has a simple solution, adding the word “foreseeable.”

There are other changes proposed in the same vein that I won’t go into here. In some areas our coalition would have proposed different language to address the problems. But the overall point is: these are the changes needed to fix core problems in the bills and bring them into alignment with mainstream medical and scientific recommendations. The House Democrats did not go back to previous, more ambitious reform proposals. They took the House bill and tried to fix it on its own terms. On the difficult issue of pre-emption – whether and how the new federal law should affect state laws – they took a particularly accommodating approach. They left that part of the redline blank with a note that it should be negotiated last – after the parties had agreed to the details of the federal program.

There are other changes proposed in the same vein that I won’t go into here. In some areas our coalition would have proposed different language to address the problems. But the overall point is: these are the changes needed to fix core problems in the bills and bring them into alignment with mainstream medical and scientific recommendations. The House Democrats did not go back to previous, more ambitious reform proposals. They took the House bill and tried to fix it on its own terms. On the difficult issue of pre-emption – whether and how the new federal law should affect state laws – they took a particularly accommodating approach. They left that part of the redline blank with a note that it should be negotiated last – after the parties had agreed to the details of the federal program.

Chemical industry’s true intentions revealed

Rejecting the proposal and the offer to negotiate categorically suggests that the industry is not the slightest bit serious about achieving an actual compromise on reform, but that they are every bit serious about running the table. For a full year they have tried to pin the “hold-up” on the Senate bill, the Chemical Safety Improvement Act, entirely on Senator Boxer, the chair of the Senate committee. Because the Senate bill is bi-partisan, and Senator Boxer is known as a strong defender of California, the argument has had some traction. She has indeed moved cautiously. Yet here was a clear opportunity to address the core, basic problems shared by both bills and even negotiate over pre-emption, but it was rejected out of hand by the chemical industry. Why? And why publicly focus on the Senate at exactly the moment when the House could move forward if the industry negotiated?

I think the answer is that getting a number of prominent Democrats on the deeply flawed Senate bill a year ago was a major coup for the industry. It muddled the issue and gave the coveted mantle of “bi-partisan” to a very one-sided proposal. They want to preserve that muddle going into a new year so that in the event that Republicans take the Senate, they can move a bad bill rapidly. In the event that they don’t, the continued presence of key Democrats on a bad bill would make it harder to move a good one forward.

What’s happening in the Senate

Senator Boxer reportedly shared her own redline of the Senate bill with Senators Vitter and Udall about a month ago. Theoretically, the moment for a real negotiation in the Senate is at hand. I hope it is. We will certainly evaluate any proposal on the merits. But because of what just happened in the House, I fear that instead we will see an effort to surface a reworked version of the Senate bill that still doesn’t fix the core issues coupled with a full-court press to get new Senators to endorse it nonetheless. The chemical industry will be helped in that effort by an unprecedented political spending spree. In addition to the traditional campaign contributions and lobbying, the effort includes even more of the nauseating “issue ads” that debuted in the last election cycle. (These ads don’t have to be reported. Our colleagues at EWG cataloged the more conventional, trackable spending here.)

What’s next

The chemical industry’s hard line combined with its enormous war chest and our increasingly corrupt times suggest that meaningful reform – that protects public health – is unlikely in the near term. That is hard for me to say out loud given my own investment in this issue. Yet, if we take our eyes off of Congress, the possibility of patently phony reform – that does more harm than good – is high. We – the big WE of everyone who genuinely cares about this – will have to continue to walk and chew gum at the same time. We will need to remain organized nationally even as we look to states to again lead the charge with new policies that protect public health. We’ll need more action by retailers and other players in the marketplace – like Kaiser Permanente who just banned toxic flame retardants from their facilities.

The odds seem long but they may be pretty good. The chemical industry has money but it lacks credibility with everyone who doesn’t rely on it for campaign contributions. (And even some that do.) Everything they have done in the last year has only further undermined their credibility outside the Beltway. And the recent defeat of Eric Cantor – in whom the ACC invested $300,000 dollars – should remind members of Congress that money isn’t everything.

The odds seem long but they may be pretty good. The chemical industry has money but it lacks credibility with everyone who doesn’t rely on it for campaign contributions. (And even some that do.) Everything they have done in the last year has only further undermined their credibility outside the Beltway. And the recent defeat of Eric Cantor – in whom the ACC invested $300,000 dollars – should remind members of Congress that money isn’t everything.

And while we all do what needs to be done to protect public health and the environment, it should be mildly encouraging that our colleagues in Europe continue to move forward. The European Union is continuing to implement their pioneering chemical policy that is already setting a new standard for the world.

Denmark, it appears, may be fine. Something is rotten in Washington.