Action Taken in Minnesota Benefits People in New Mexico

Proponents of the Udall-Vitter legislation having been making an argument that goes something like this:

“Only a few states have chemical laws and only they are affected by the bill’s restrictions on states. People in New Mexico don’t have their own policies or benefit from these laws, so the bill is a good deal for them.”

This statement is flat-out untrue and betrays a lack of understanding of how state policies have worked and the effect they’ve had. I’m not accusing the Senators who’ve made this argument of bad faith, but I’m sure their misunderstanding has been cultivated by the chemical industry.

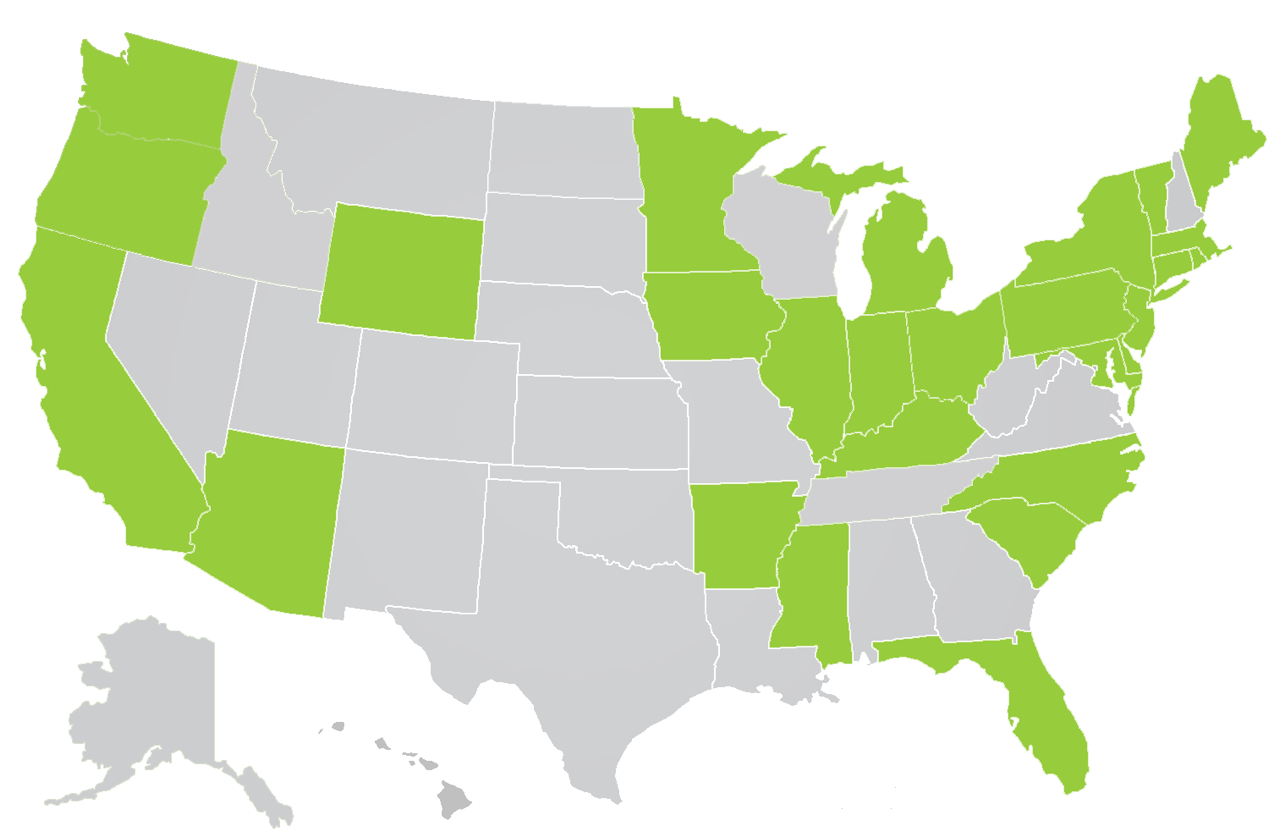

Most of the progress that has occurred at the state level over the last ten years has had to do with disclosing or restricting the use of a toxic chemical in a consumer product. That has often led the companies that make the product to remove or restrict the chemical nationwide. It’s simpler than trying to make a safer product for Minnesota and a dirtier one for Wisconsin, and also a lot more defensible. Consumers across the country – including in New Mexico – have benefited from the reductions in their exposure to toxic chemicals prompted by a handful of states.

What am I talking about? You may have heard of BPA (bisphenol A), the chemical that acts like a sex hormone and harms children (and the developing fetus), throwing off their development and increasing their risk of an array of diseases. In spite of these problems, the fancier kind of baby bottles used to be made with BPA. (The plastic looked better and felt more durable.) Then Minnesota banned baby bottles with BPA. Several other states followed suit. The nationwide market changed – and an absurd risk to children was eliminated because of the actions of a few states. Maine required companies merely to report the presence of certain chemicals, including BPA, in children’s products in the state. That prompted Hasbro to design its toys to avoid the use of the chemical.

What am I talking about? You may have heard of BPA (bisphenol A), the chemical that acts like a sex hormone and harms children (and the developing fetus), throwing off their development and increasing their risk of an array of diseases. In spite of these problems, the fancier kind of baby bottles used to be made with BPA. (The plastic looked better and felt more durable.) Then Minnesota banned baby bottles with BPA. Several other states followed suit. The nationwide market changed – and an absurd risk to children was eliminated because of the actions of a few states. Maine required companies merely to report the presence of certain chemicals, including BPA, in children’s products in the state. That prompted Hasbro to design its toys to avoid the use of the chemical.

Other examples include restrictions on:

- brain-toxic lead and cadmium in children’s jewelry (e.g., Washington),

- mercury in thermometers and novelty products (e.g., Louisiana),

- hormone-scrambling phthalates in toys (e.g., Vermont),

- cancer-causing flame retardants in couches and electronics (multiple states), and

- cancer-causing formaldehyde in wood products (e.g., California)

The list goes on. In some cases, such as with phthalates, the federal government eventually followed suit, but in many, the state standard changed the market, reducing exposures to toxic chemicals even in states where local officials never lifted a finger.

And that’s why the issue of future state actions is so important in the Udall-Vitter bill. It’s not that state actions have been overwhelming. The pace of them has quickened, but it is still modest. But the Udall-Vitter bill, as currently drafted, would block future state actions when EPA merely begins an assessment of a chemical. That step is 5- 7 years away from actually restricting that chemical under the bill. Attorneys General have described that time period as a “regulatory void” where the public isn’t protected. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has called it a “death zone.” As he noted at a recent hearing, the industry has many tools – lawsuits, legislative riders, political pressure on EPA– to lengthen the “death zone” even beyond the 7-year deadline in the bill. The chemical industry will have both the motive and the opportunity to force a delay.

The choice presented by the bill is a false one. The pace of EPA chemical reviews under the bill is very modest, arguably more modest than the recent pace of state action. The first does not require the cancellation of the second. The solution to the problem is fairly simple: amend the bill so that no state is blocked from acting until and unless EPA has taken its own action to restrict a toxic chemical.

The chemical industry would like “uniformity” in the treatment of toxic chemicals. Reasonable people may support a uniformity of “something.” The bill creates an extended period for a uniformity of “nothing.” There is no net benefit in public health or environmental protection for people in New Mexico or other non-active states from such an approach.

Share this on Twitter

Read this: http://t.co/gE0iyKDVZD What Senators Aren’t Getting About State Chemical Policies #RealReform #TSCA pic.twitter.com/huvxYo8Jg6

— Safer Chemicals (@SaferChemicals) March 30, 2015